The ancient Minoan palace of Knossos lies just five kilometers (three miles) southeast of Heraklion, the capital of Crete. It covers an area of about 5 acres and has over 1000 rooms.

The earliest settlement on the site has been traced to the neolithic period of about 6000 BC. The palace period began about 2000 BC.

Originally the palace had three or even four floors. Arthur Evans, who discovered the palace, had some sections reconstructed. When he was working in the early part of the 20th C, archaeology was not as advanced as it is today. Some of the things he did would not even be permitted nowadays. But the reconstruction certainly allows us a glimpse of how the palace might have looked in its heyday.

A complex site

What you see when you visit the site is far more complex than you might at first imagine (and it looks complex enough anyway!).

The palace was destroyed on a number of occasions, and then rebuilt. It is thought that earthquakes were to blame each time it was destroyed.

The palace is known to have been occupied from 2000 BC to 1400 BC, and there were three distinct phases. The first palace lasted from 2000 – 1800 BC, the second from 1800 – 1700 BC, and the third from 1700 – 1400 BC. What you see when you visit are mostly the remains of the third palace, which was also the most advanced and complex.

Was it the labyrinth of King Minos?

Myth, legend and history often blend together in these ancient times, and historians have difficulty in separating them. Even when they do separate them, they then have trouble convincing us they are correct, as most of us actually like to believe some of the fascinating stories of long ago.

Because the floor plan of Knossos is so complicated, the theory has been put forward that the palace was in fact the labyrinth of the legendary King Minos. One detail used to back up this theory is that the Minoans’ symbol – found in many places on Crete – is the double headed axe. The Greek word for this axe is ‘labrys’, closely related to the word ‘labyrinth’.

Exploring the palace

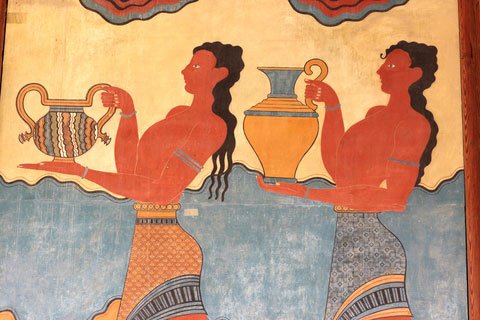

You enter the palace complex by the West court. Make your way to the south propylaea through a large gateway. You’ll see a lot of storage rooms, some containing large clay pots, or pithoi. You’ll find yourself in the large central courtyard. It is thought that this is where the ‘bull leaping’ took place. (Bull leaping is illustrated on a number of frescoes.)

On the west side of the courtyard you can find the grand staircase, and the throne room, containing the so-called throne made of alabaster.

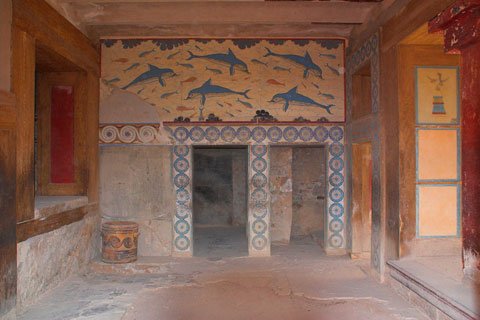

On the east side are what are believed to be the residential quarters, with utility rooms, bathrooms and toilets.

You’ll also see a hall; look out for the double headed axe symbol carved on its pillars. Next to the hall are the bedchambers of the King and Queen.

Although it’s good to see the frescoes decorating some of the walls, remember that these are replicas. The originals are in the Archaeological Museum in Heraklion.

You don’t see all the site

The site of Knossos is vast, and visitors are only allowed to see part of it. Even so, it’s still plenty to take in. The best way to tour Knossos is to have a guide, or get hold of a good guide book with a detailed plan. Use this as you tour the site, and you’ll get much more out of your visit than just aimlessly wandering around.

Who discovered the Knossos site?

Popular history credits Sir Arthur Evans as the guiding light of discovery and excavation but the Historical Museum of Crete has a manuscript by Minos Kalokerinos that describes his finding of part of the palace six years earlier than Evans.